🧠 People who struggle with boundaries often assume there’s some innate ability they’re lacking. There isn’t. Boundaries are a skill anyone can build, but not by consuming more advice. They’re built through deliberate practice.

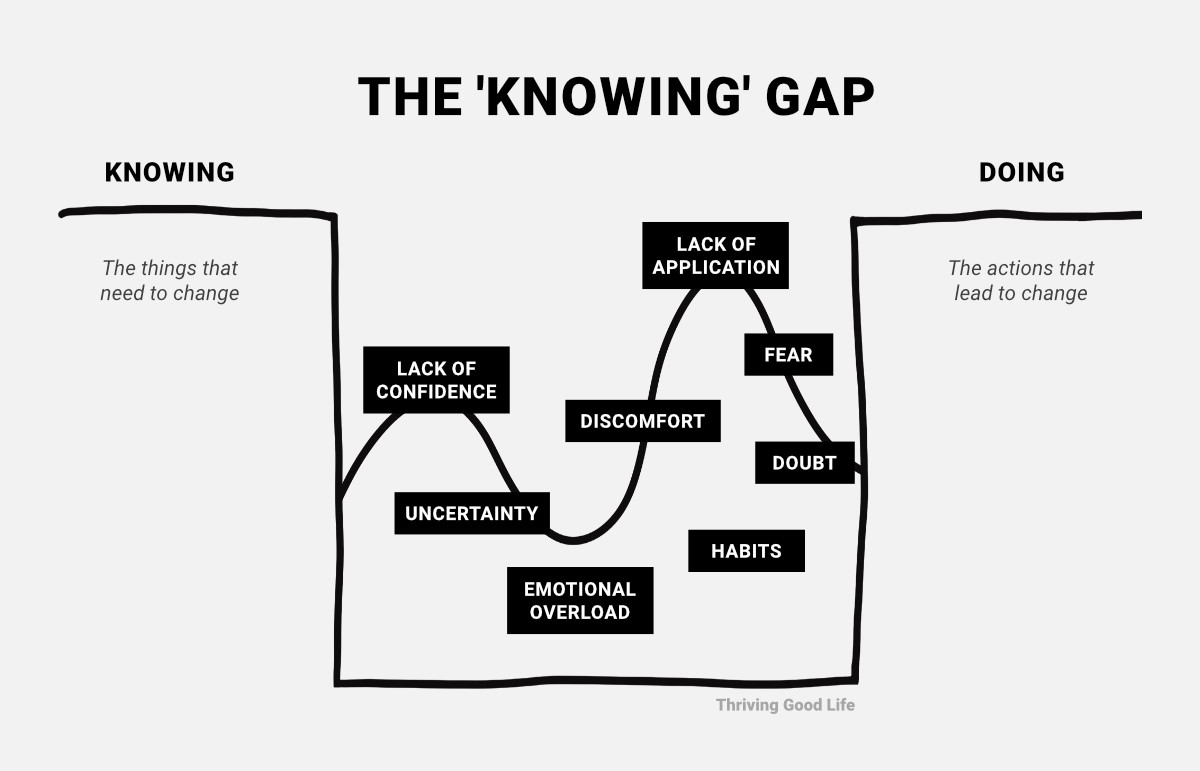

Most of us know we need to set better boundaries. Yet they often crumble the moment discomfort enters the room.

The gap isn’t a lack of knowledge.

It’s not a lack of willpower either.

The ‘knowing’ gap lies in something most boundary advice doesn’t speak about enough: Practice.

Why Boundary Advice Fails When It Matters Most

We’re swimming in a sea of advice: books, articles, YouTube and podcasts explaining what healthy boundaries look like and why they matter.

Most of it focuses on quick tips, pre-written scripts and mindset shifts because they’re easy to share and make great sound bites. “Just say no.” “Raise your standards.”

The slower, less interesting work of practicing, fumbling, and trying again rarely gets mentioned. Even though that’s where real change happens.

What actually gets in the way between knowing and doing.

You can know how you want to be treated and still tolerate moments when your mom/friend/boss crosses or violates that line 1.

Say yes when you want to say no.

Stick around when someone keeps disrespecting you.

Old patterns kick in. We react before we think, defaulting to what we’ve always done out of fear, discomfort and a whole host of other internal blocks.

And when the boundary pusher is someone we love or can’t easily walk away from, the stakes for upholding our boundaries feel even higher.

Reflection Alone Won’t Build Boundaries

Once you’re able to identify these patterns and see them play out in your life, you start to understand what’s at the root of any boundary issues. Great! And then what?

This cycle of acquiring knowledge and constantly reflecting on why we struggle doesn’t make us better at holding boundaries. Putting in the reps does 2.

Strong boundaries 3 grow through the everyday work of learning how to speak up, how to stand your ground, and stay connected to your values.

Most people don’t have boundary problems. They have practice problems. Call it boundary reps. The unglamourous work of repeating the behavior until it sticks to your identity.

Think of it like training a muscle. The first time you try a push-up, your arms shake. You might not even make it all the way down.

But after 20 reps? 50? 100?.. Your body knows what to do without thinking.

Boundaries work the same way.

The first “no” feels impossible.

The tenth feels normal.

The fiftieth becomes automatic.

The roots matter. Past trauma, conditioning, power dynamics all shape how we manage interactions with others.

But understanding the struggle, and developing the skill to set and hold boundaries are two different things.

We may not be able to change the root causes, but we can build new patterns through repetition.

Boundary Skills Are Learned, Not Innate

A friend once told me she had no boundaries.

Over the years I’ve come across people who said the same thing.

I always wondered about that because boundaries aren’t something you instinctively have. They’re something you work on.

Boundary skills, like assertiveness, are built through repeated real-world practice, reflection, and feedback. It’s not innate. It’s learned behavior.

Developing the ability to express needs and set limits clearly is part of how healthy boundaries take shape and strengthen over time 4.

When people think about boundary struggles, the first thing that comes to mind is the people pleaser. The person who can’t say no, or who puts up with being treated poorly.

That’s not the case for me.

I say no. A lot.

And I don’t tolerate other people’s nonsense.

If someone violates a boundary with me, I’m done.

But for years, I had a different boundary problem: I couldn’t stop myself from jumping in to fix things for people who didn’t ask.

I took on a lot of family responsibility from a very young age, and it set me up to be a caretaker. A fixer. A rescuer. I learned early that keeping the peace and helping others, even without being asked, was how I showed care, earned trust, and received praise.

That role became ingrained, shaping my default way of being in relationships.

And I relished it. My whole identity wrapped around being the responsible one who always had a solution. So naturally, I pushed my ‘care’ onto others.

Years later, through journaling and studying psychology, I could see why I was like this. I could tell you the psychological and relational dynamics that this behavior stemmed from.

And yet, even with that self-awareness, I still did it.

Understanding the ‘why’ didn’t stop the impulse to jump in. Practice did.

I made one rule: don’t offer advice unless someone asks.

Then I practiced catching myself and course-correcting in real time.

How to Practice Boundaries (For Real)

Practice works because it trains your responses, not just your thoughts.

Each repetition teaches your brain and body a new way to handle pressure. But random, half-hearted attempts won’t cut it.

The practice has to be sustained and deliberate.

Deliberate practice means more than memorizing scripts and comebacks. You’re observing, planning, and adjusting each time.

You’re building skill through repetition with feedback, even if the only feedback is how your body feels before, during or after an interaction.

And after you’ve spent time practicing:

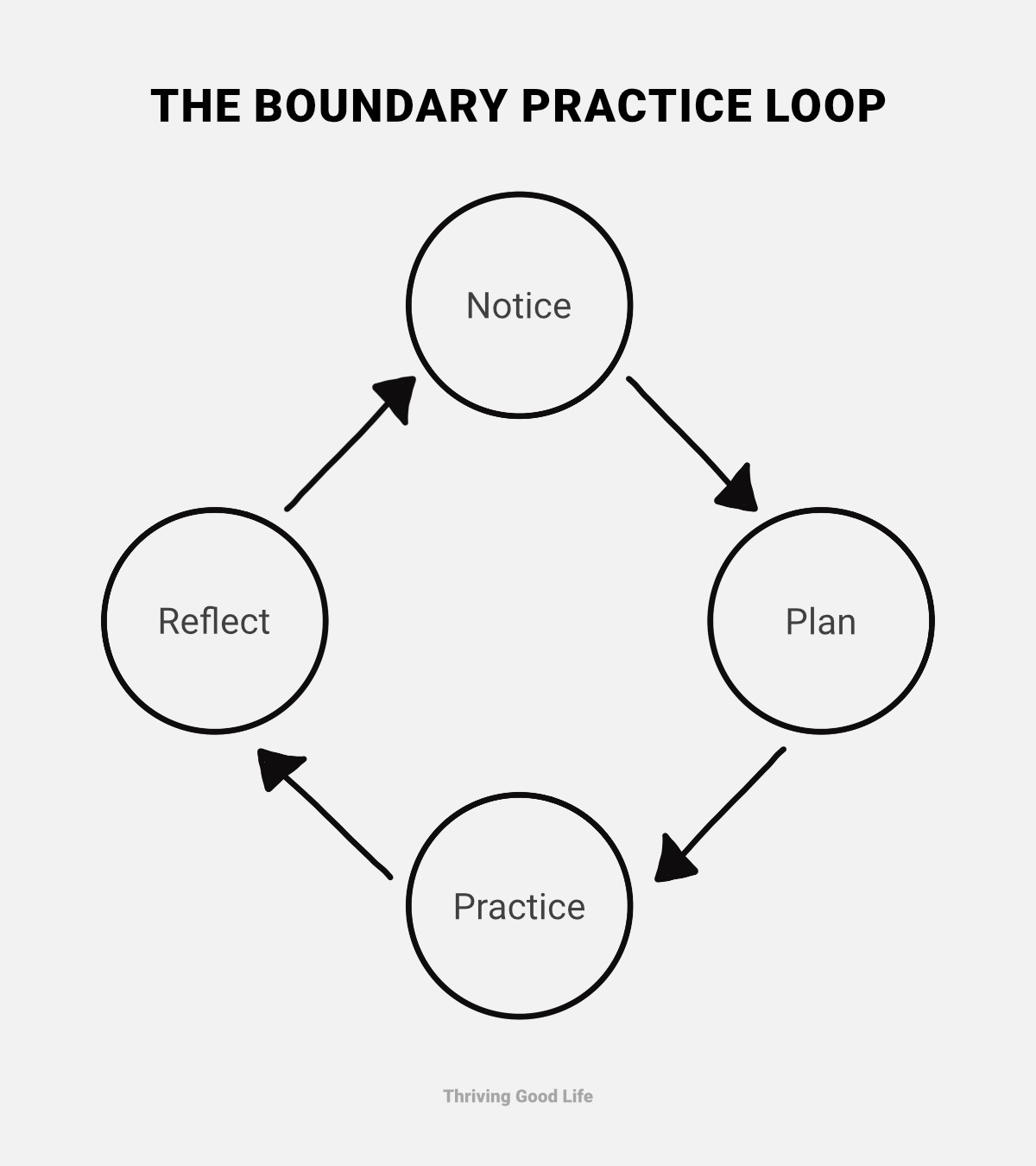

The Boundary Practice Loop

Boundary practice is a loop: you notice, plan, practice, reflect, and then repeat with more confidence next time.

It’s a simple way to move from awareness to action.

1. NOTICE: Identify a specific boundary moment.

Pick one situation that regularly leaves you feeling uncomfortable or resentful.

It might be saying yes when you’re already exhausted, avoiding a conversation because you don’t want conflict, or brushing off a comment that hurts.

2. PLAN: Make an if–then plan.

Planning your response in advance helps your brain link a cue to an action. Unlike generic scripts, these if–then plans (called implementation intentions) are situation-specific.

They create strong mental links between your unique triggers and your chosen responses, making the desired behavior happen more automatically 5.

Each if–then plan is a mental rehearsal that prepares you for the real moment.

You’re giving your brain a map to follow, so when you’re under pressure you’re not scrambling for the right words.

3. PRACTICE: Rehearse the response.

Try it in smaller, lower-stakes situations first.

The point is to practice following through on your plan, not perfecting what you say. So, the more you do it, the less uncomfortable it feels.

4. REFLECT: Reflect and Track what happened.

After each attempt to practice a boundary, write down what you noticed.

What worked? What didn’t? How did your body react?

Written reflection gives you something concrete to work with, not just thoughts circling in your head.

And tracking small wins, even the messy ones, increases your belief that future you can indeed do this 6.

Over time, you’ll notice how the silence after a firm ‘no’ feels freeing, not guilt-ridden.

5. REPEAT: Adjust and try again.

The first few reps might feel shaky or awkward. With practice, you’ll find your words faster, your tone steadier, and your recovery quicker.

Small boundaries, like declining a casual favor, will start to feel easier within weeks.

Deeper patterns, especially with family and close relationships, can take longer. There’s shared history, so the emotional stakes and consequences are higher.

The timeline matters less than the consistency.

A few deliberate attempts each week will build skill faster than waiting for the right moment to practice, or trying once and giving up.

Over time, boundary skills build through noticing, planning, practicing, and reflecting.

These steps aren’t meant to be followed perfectly, or in the same order every time.

In some situations you might reflect first before moving on to planning.

What matters is that each pass through the loop strengthens the response.

Practice doesn’t guarantee others will respect your boundary. What it does is strengthen your ability to say “wait a minute, that’s not what I want.”

And then not backing down when someone ignores or tries to guilt-trip you into changing your mind becomes easier. You’re also learning to manage your own impulses when they try to pull you back into old patterns.

A Tool for Putting this into Practice

If you want stronger boundaries you have to create a habit around them. The Practice Builds Boundaries Journal gives you structured tools to do just that.

28 weeks of guided pages help you observe and practice your boundaries, plan your own If–Then responses, and reflect on what you’re learning along the way.

It’s designed for deliberate practice, not perfection. For building the skill, confidence, and self-trust that come from putting in the reps.

Join the Reflect & Thrive Newsletter

Bi-weekly notes on self-management and the choices we make

This newsletter won’t fix you. But it’ll help shift how you see things, respond to others, and show up in relationships and everyday interactions.

Footnotes

- There’s a difference between crossing and violating a boundary. Crossing means overstepping without realizing. Worthy of giving them a chance as long as they respect you addressing the issue, and show willingness not to repeat it. Violating means a serious, non-negotiable breach. No second chances.

- Mendelsohn, A. I. (2019). Creatures of habit: The neuroscience of habit and purposeful behavior. Biological Psychiatry, 85(11), e49–e51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.03.978

- Chernata, T. (2024). Personal boundaries: Definition, role, and impact on mental health. Personality and Environmental Issues, 3(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.31652/2786-6033-2024-3(1)-24-30

- Speed, B. C., Goldstein, B. L., & Goldfried, M. R. (2017). Assertiveness training: A forgotten evidence-based treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), 1–20. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cpsp.12216

- Wieber, F., Thürmer, J. L., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2015). Promoting the translation of intentions into action by implementation intentions: behavioral effects and physiological correlates. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9(395). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00395

- Cleare, A. E., Gardner, C. D., King, A. C., & Patel, M. L. (2024). Yes I can! Exploring the impact of self-efficacy in a digital weight loss intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 59(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaae085